Monsters Within: Matt Lee Interviewed

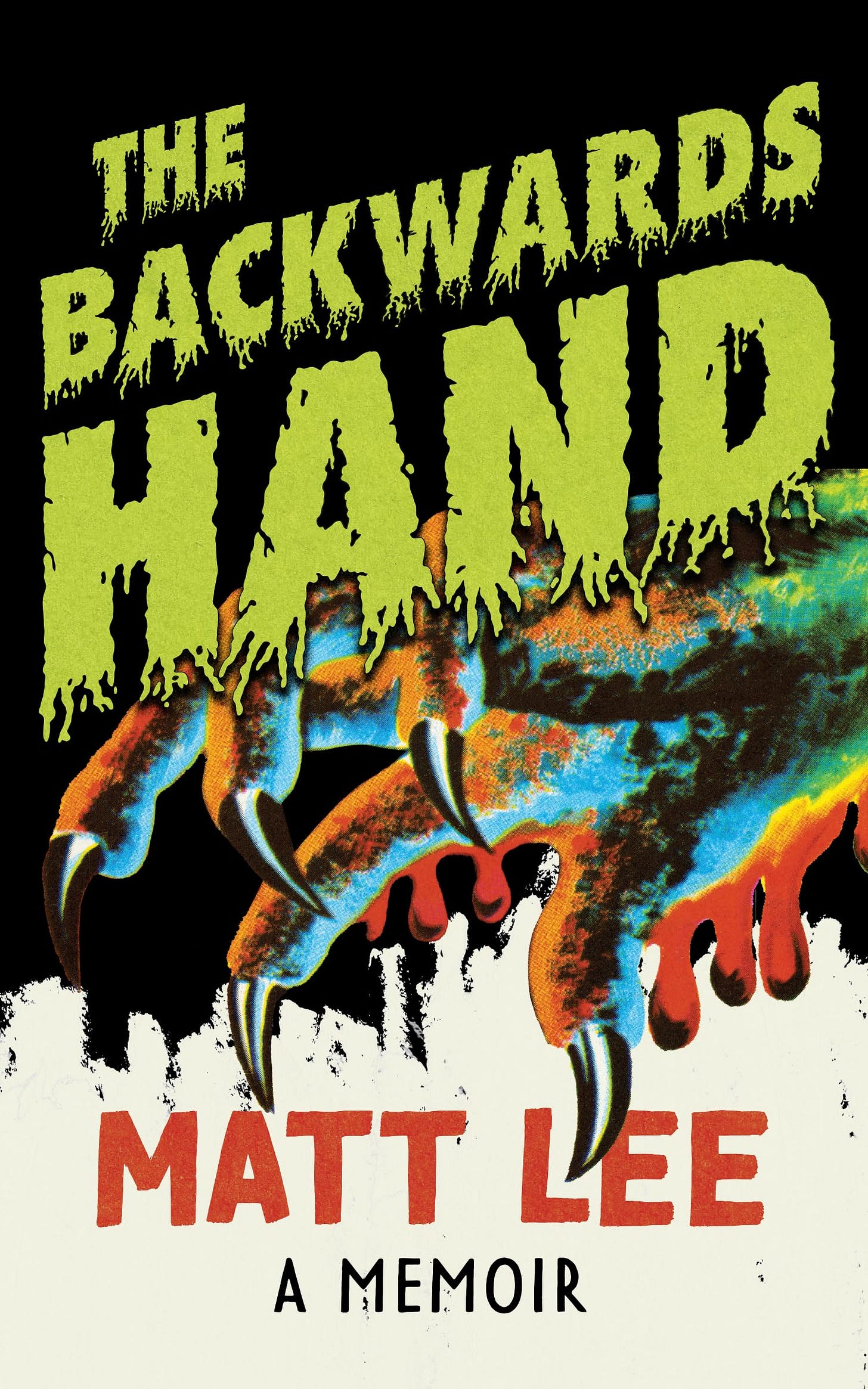

A conversation with author, Matt Lee, about his memoir, THE BACKWARDS HAND.

I re-read Crisis Actor earlier in the week, so forgive me if I reference something that was in Crisis Actor and not The Backwards Hand. There’s a lot of information in your books. Where does research play in? How much of this is in your brain, ready to go?

The research is always a big part of the process, as you pointed out and, for me… I’m kind of a nerd, and that’s the fun part: chasing down all these sources. It’s a toss-up, I think. When I approach a project, whether it was Crisis Actor or The Backwards Hand, it began with certain touchstones that I was already familiar with. Either, an event, a person, an artist, a historical episode, a book, something that, for whatever reason, just lodged itself in my brain. I start to follow that and build off of that, so I think part of the fun is finding the connections.

Once I kind of have an idea of the subject. So like, Crisis Actor, the frame of the whole project was really, “let’s equate art and terrorism and see where that takes me.” For The Backwards Hand, it was “let’s equate disability and monstrosity and see where that takes us.” I kind of cast a wide net. I’m like a whale taking a huge gulp of seawater and syphoning out all the krill or something. It always surprises me, the things I manage to dig up, that I wasn’t familiar with from the get-go but still tie into certain obsessions I already have.

I’ll give you an example from The Backwards Hand. One of the key films referenced in that book is Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now; a film I had long admired, always held to very high esteem. All of his films, but especially Don’t Look Now, I think one of the few films that really instills a sense of terror in me any time I watch it. Looking into that and then also wanting to write about the British musician, Robert Wyatt, knowing that he is a wheelchair user. I know that, going into The Backwards Hand, I wanted to touch on both of those. Come to find in researching both, that Wyatt’s wife, was the assistant editor of Don’t Look Now—which I did not know—Wyatt went with her to Venice while filming, right before his accident, when he fell out the window and became paralyzed. Those kind of connections always blow my mind.

The research always threatens to overtake me at times, so I always try to break it down. Like with Backwards Hand—I always feel like I’m completely insane when I explain this—I created color-coded documents to sort of help me visualize it. “Here’s anything from horror films, it will be the color red. Here’s anything from researching Diane Arbus. Here’s anything from Freakshows in America in the early 20th century.” Just trying to keep everything organized. Once I have it all compiled start to put everything together. The research for these projects is always pretty time consuming. I think Backwards Hand, when I looked at the final list of sources, I think it was more than 300 books, articles, and things.

It's a solid chunk of notes at the end of the book.

The notes section was added kind of at the last minute. Right when I thought I was done, the editor was like, “what do you think about putting a notes section in here?” And it became, kind of, the book within the book because it kind of is its own beast. But I had a lot of fun putting it together, and I think it complements the book and, hopefully, gives readers a better jumping-off point if there’s something that resonates with them in the book, they wanted to learn more about.

So it sounds like it’s an equal amount of research that is already aided by the way your brain works and what you enjoy to ingest in terms of information—or not even enjoy, but just what interests you.

It’s pleasurable. I get off on it.

I feel like I learn so much when I read your books, and, ya know, I really love horror movies as well…

I didn’t know that about you, Max! I’m surprised to learn that.

Yeah, well what can I say, I try to keep it private. You don’t only talk about how these movies relate to the subject at hand, but your experience first seeing them. We’re around the same age. I can remember AMC’s 100 Scariest Movie Moments.

Yeah, that was huge.

That was enormous for me. That was how I first learned about Don’t Look Now. There’s something really interesting in your book… How old were you when you first saw Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Cuz I was an adult when I first saw that movie and I don’t know if I would have appreciated it as a kid, but I also don’t come from a family of artists in the same way that you do, so maybe that has something to do with it.

I was in elementary school, probably 8 or 9 maybe, so pretty young. It was funny. We’d always go to the video rental store, and I was always drawn to the horror section. Usually, my mom wouldn’t let me get anything R-rated, yet if it was an old movie—if it was a classic, black and white movie, that was okay. So that’s how I saw Hitchcock’s Psycho, which an elementary school kid shouldn’t be watching necessarily. That’s another one that probably went over my head when I first saw it—movies like that, and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane was absolutely one of them. I think, strangely enough, my grandmother watched that movie with me because she loved Joan Crawford. When you’re that young and watch a film that deals with those very adult themes, those are the films that really stayed with me even though I didn’t really have the tools or the experience or the language to process a film like that.

It's very emotionally intense, that movie.

Yeah, I mean, that movie is fucked up.

It really is! The end, on the beach, is fucking terrifying. It’s so scary, but maybe not necessarily in the way a child might think something is scary.

Well as a child, seeing a character that has regressed into childhood and hasn’t been able to escape childhood. That was kind of frightening to me. Like you could be stuck in a perpetual childhood. It’s like Peter Pan gone wrong. I think you’re right, the final sequence on the beach is more frightening than any of the torture or captivity stuff. Also seeing a film like that, how a family can turn on you, that is also quite frightening for a young person: that the people who love you can be the ones that hurt you.

Watching those films at such a young age really affected me, and I think kind of made me want to go further. I think that’s where a lot of the obsession with horror began.

I feel like that’s kind of a big part of horror. You’re like “alright I’ve done this one. What is the next level?”

You’re always chasing the dragon.

Exactly. “I’ve seen Night of the Living Dead, now I need to see The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.”

Especially, when you’re younger, it’s a glimpse into a forbidden world, something that is off limits, and I think there’s an innate attraction to that. “I’m watching something I should be seeing,” and the thrill of that is really magic. And, like you said, you wanna chase it, you wanna capture it again.

And it’s interesting because that kind of ties into the idea of how [the concept of] abjection works throughout The Backwards Hand. Like, you don’t make it out to be that disability is a societal spectacle. It’s in a horrible kind of way that society makes it one.

Yeah, I think you’re absolutely right. Abjection, for me, became a way to explain how disability became conflated with monstrosity. The idea of The Monster is kind of a blank slate. You can project your whatever own personal fears and anxieties are into the conception of what the monster is. So, I think everyone has their own unique way to define what makes a monster. On the other hand, abjection is this universal phenomenon. We’ve all felt it and we’ve experienced it in a similar way, because the trigger is always the same. When you see a dead body. When you see something that confronts you with the very limitation of life itself—which a crippled or disfigured body will do, you will respond to it, and I think people respond to it in very similar ways. Fear, anxiety, discomfort, pity, typically in a negative way. To me that was the key; oh this is why—not even just in horror films, but in looking at classical paintings, or going back into Greek mythology. Going way, way back, this idea of the corrupted body, the disfigured body being equated to a monster, or something to be afraid of. That was, to me, a revelation.

And then you have people like Tsutomu Miyazaki. In a DM, you told me that you wanted to treat him like an evil version of yourself throughout The Backwards Hand, and I can see the similarities. Something that I noticed is that both his sequences and your sequences are written in the present tense.

Yeah, he’s kind of the photo-negative—like you said, my evil doppelganger. He was another person who I was familiar with even before I began writing the book, and had only heard of him through the Guinea Pig films.

His ties to being a fan of them?

Yes, which were kind of misrepresented and exaggerated. Watching the Guinea Pig films is one of those… “okay, lets watch extreme horror,” the Guinea Pig films always pop up. Reading about the moral panic that arose from Miyazaki’s crimes being tied to those films was interesting, but I hadn’t realized he was disabled until I started writing the book. Again, he wasn’t going to be part of it originally, but I did want to write about the dismemberments and amputations in Guinea Pig. When I started to take a closer look, his name popped up again, and I was like “oh yeah, that guy, the notorious child-murderer, serial killer, cannibal,” and I caught someone writing about his hands, and was just completely taken by surprise that we had this, not only very rare but very similar condition. He doesn’t have my exact condition, but similar limited mobility of his hands caused by fused bones. Learning that freaked me out, just the coincidence of it. I started researching more and more about him and those similarities kept popping up: he was a huge horror fan, loved slasher movies, loved comic books, wanted to be an English teacher. Even our birthdays are only a couple of days apart. Just weird coincidences like that.

Again, it was just sort of a happy accident that I found that and was able to work him into the book. I liked treating him as sort of the boogeyman within the book. Even if you disregard the fact that he was disabled, he’s like a real-life monster. It doesn’t get more horrifying than abducting little girls, chopping them up and eating their body parts.

And then taunting the parents…

Yes, then his whole campaign to terrorize the victims’ parents, writing poetry to them, really nightmarish stuff. Adding to that that he was disabled really complicates it. The book is full of monsters, right? Some of them are disabled, some of them are able-bodied, some of them are imaginary, some of them are real. He just became the perfect example of a real-life monster who also happened to be disabled. Where it gets sticky is, he sort of said, “well, I turned out this way because I had such a horrible childhood, and everybody made fun of me, and I was such a loner because I had this disability.” He kind of put some of the blame on that. So again it’s “what makes the monster?” Did the disability contribute to it? Is it beside the fact? These kind of difficult moral questions that I had to kind of wrestle with. Disability or not, everyone is capable of behaving in a monstrous fashion.

An enormous part of the book is about the Nazis, who we can say were by-and-large not disabled. One of the things about your book that really stayed with me, which is something that I think really stayed with you as well… There’s only one picture in the book.

Yeah, Richard Jenne.

There really are no words for that picture. I’m not a religious person. My mother is Jewish, so there is a part of me that personally connects to the Holocaust stuff. It’s just the perfect example of utter human monstrosity.

Yeah, that photograph, again another one I stumbled across in the research phase, and really the entire Aktion T-4 euthanasia campaign was something I was pretty unfamiliar with, and I think is often overshadowed by the extermination of Jews during the Holocaust; we’re talking millions of people killed as opposed to hundreds of thousands of people killed. When you’re in school and you learn about the Holocaust that’s always the focal point.

It's easy to make it a focal point but that doesn’t excuse not discussing the totality of it.

It’s difficult to wrap your head around, right? When I started diving into T-4 and how it fed into the mass extermination of Jews. Really, they “perfected their methods,” if you will, on disabled inmates; learning how to use gas, how to efficiently and effectively conduct mass-killing on this industrial-level scale, which they then took and used on a grander scale.

With Jenne, finding that image… It’s a photograph that really haunts me and really stayed with me. I was sort of stunned when I saw it. When I was wrapping up the first draft of the manuscript, my wife was pregnant with our son. So, again, I think it just hit closer to home as an expectant father. That a parent would willingly give up their child to be killed because they were born with a disability. When I found that picture, I knew I had to share it. I needed to reader to experience that with me. It’s a very powerful image.

You write in very plain language, which I think makes your prose very impactful. It’s delivered in, kind of, punches of information, but it’s one line right above the picture: I need you to look at the last photograph taken of Richard. It’s like being hit by a truck.

I’m glad you said that because that was my exact, intended effect. After you’ve been confronted with a deluge of text and information, just to have this image. I hope it really kind of stuns people sober. It really puts a face to it.

It’s a very sad story. Even just learning about the woman who killed him in the asylum where he was. The T-4 stuff was one of the harder parts of the research. Just how this woman could callously… she killed hundreds of children with lethal injection. In the same way you pointed out that the language I employ is very stripped back and bare and plain-spoken. You read a lot of these accounts from the perpetrators of these atrocities and they are similarly very plain spoken and direct about these crimes against humanity that they committed. So, like, she’s talking about killing hundreds of babies without batting an eye. You come to find out that many of these people just got a slap on the wrist. I think that particular nurse got a few months in jail and was then released despite being a mass murderer.

Sadly, Richard Jenne is just one of hundreds of thousands of disabled people who needlessly lost their lives, simply for the crime of being born differently.

Something else that you point out is that the Nazis actually sited an American court case as their defense during the Nuremburg trials.

Yes, it’s just layers and layers of horror, and it all has a legal precedent. Buck vs. Bell, that supreme court case… Even being a disabled writer, a lot of this was so new to me. There’s such an amazing wealth of information out there, much of it is very unsavory and unpleasant, so it tends to get swept under the rug, and people maybe don’t want to know about it because it’s so difficult to even try and comprehend.

I started with the T-4 program and the Nazis, and then sort of worked backwards into the American Eugenics Movement, which I was not terribly familiar with. It’s just wild—I mean it’s mind-boggling, the sort of “logical precedent” that was set right here in the good ol’ US of A that then the Nazis adapted to their own means. You can keep tracing it back. A lot of the eugenics stuff really goes back to the Atlantic Slave Trade. That whole idea of breeding humans to sort of “perform better” it all comes out of that, this whole pseudo-scientific field. And of course it becomes applied to anyone who isn’t a straight white male, basically. It was applied to women, people of color, and the disabled on “scientific grounds.”

The people who were perpetrating these crimes, at least from my perspective, need a way to justify it, because what they’re doing is evil. They kind of co-opt science as a way to explain “well yes, I’m suggesting we kill this person, but it’s for a very sound, logical reason, and it’s going to have a positive outcome for society.” That’s how they kind of framed these atrocities. And that idea was very popular, that you could eliminate physical imperfection through eugenics. It’s complete nonsense, that we could sort of breed ourselves out of disability the same way you might breed dogs to have certain traits.

You still kind of see this logic today even though we’re talking about things that happened over 100 years ago. It’s not only on these scientific grounds. To me the most disturbing logic is putting on fiscal grounds. It’s all about money. “We’re gonna eliminate your life to save money.” That was a big part of Buck vs. Bell. “These people, we can’t really do anything to help them. It’s going to take a lot of resources to take care of these people. We could put that money to much better use, so let’s have mercy on these people. They’re suffering. Their existences are pure misery anyway. So everybody wins. We’re gonna end their suffering, save money, build a better society by euthanizing these people. Putting them to sleep.”

Buck vs. Bell, an incredibly disturbing case when you start to look at it. It basically came down to a woman who wasn’t disabled. She was an orphan who was going through the foster care system. I might be mixing up some of the details but I believe she was a victim of rape by one of her care takers. When she got pregnant, they were sort of looking for an excuse to “take care of the problem,” and get rid of the baby. So they said, “well, she’s not of sound mind, she’s feeble minded. We need to sterilize her so she can’t get pregnant.” And it led to this whole legal precedent that, obviously effected women in particular. Pretty much any woman who ended up in an asylum… it was kind of a free for all, they could just be sterilized. Back then, it’s a much more misogynistic time. As a woman you can be institutionalized on pretty tenuous grounds. You didn’t even necessarily have to be disabled. Even learning that Buck vs. Bell has never been repealed! It's still on the books. Forced sterilizations were eventually outlawed, but the court case itself was never overturned.

To put it in a contemporary perspective… Voluntary euthanasia is a sensitive topic, but I read reports of disabled people who will opt to be voluntarily euthanized, not because they’re suffering or they’re in pain, but because they cannot afford healthcare. This is very frightening and dangerous. It directly ties back into Buck vs. Bell. It directly ties back into eugenics. The fact that money is more precious than a life. “Rather than give you the social support and the healthcare that you need, we’re gonna let you be put down to end your suffering.” I fear that it’s something, particularly in the states, that we’re gonna see more and more of. As this population is aging and as healthcare becomes more inaccessible and expensive, I think you’re going to have people whose parents hit a certain and they realize “shit I can’t afford to put my mom or dad in a long term care facility, so I guess I’ll euthanize them.”

It's a very frightening and very real precedent that I think is still ongoing.

You use the word “cripple” a lot in this book, which is not something I expected. I’m not gonna be like, “Matt, how dare you use this language,” but I am curious about what the impetus of that choice was.

I think it’s a couple of things. First and foremost, I want the book to be confrontational. I want to deliberately use ugly and offensive language that is going to make people uncomfortable, and also kind of reflect the double-standard that people still toss these words around without really thinking about how hurtful they might be. Ya know, I still hear people use the word “retard” all the time. Things like that, so I want to rub it in peoples face. The second part was that in writing the book, in coming to terms with my disability, I was also trying to embrace it. So it was kind of a reclamation of the word in the same way that “queer” has been kind of reclaimed by the LGBTQ community that can be worn as a badge of honor rather than an insult.

Diving into the disabled community, studying disability rights, its something that’s not uncommon: seeing people proudly wear this crip badge.

JG Ballard, one of my favorite writers, I think he was talking about Crash, it’s always kind of stayed with me as words to live by: In writing Crash, I basically wanted to take humanity’s face and rub it in its own vomit and then force it to look in the mirror. So I think both The Backwards Hand and Crisis Actor, that’s my goal, to rub your face in your mess and have you take a hard look at it.

People talk about the term transgressive when it comes to the literature that we trade in, that word is thrown around a lot. When I wrote Coyote, which is pretty violent—a lot about violent intrusive thoughts, being a high school kid who is like “why am I thinking about stabbing this pregnant teacher? I feel horrible about this,” but it’s still happening in my head… I didn’t want to be “transgressive” but its kinda fun to play the provocateur. There was a part of me that was like “I want some people to read this and go ‘what the fuck.’” I do want it to bother some people. I think that inherently comes from the fact that it is bothersome. You want to transplant that experience onto the audience.

I think there’s parallels in both our work, and other writers we know and follow, who get this transgressive label. It’s pushing a boundary, sort of trafficking in a counter current. I like the word “subversive” more than I like “transgressive” because what all of us are doing is sort pushing against normalcy, or these common conceptions of good taste, or morals. We’re kind of working in more of a gray zone; moral ambiguity playing a much bigger role. I think certainly in my own work, I never like to have a clearcut good and bad. I think it’s always much more murky. They’re sort of these timeless subjects that people shy away from. I think that violence, however you portray it, is one of them. It’s sort of a push/pull where you wanna look away but it’s also magnetic and you’re drawn to it.

It's interesting what you said, the example of “why am I having these intrusive thoughts about stabbing a pregnant woman” and trying to work through that. Even though, on the surface that’s so disturbing, it’s much healthier to work through something like that—whether you do it in art or not—rather than sort of try to bury it down and oppress it. I think, certainly that’s what I’m trying to do in The Backwards Hand is looking at these societal taboos, trying to air them out and put them in the open. Disability is still very much something that people don’t like to talk about. It's something that people don’t even like to think about. They’re afraid, it’s the specter of death, it's hanging above you, it’s coming from you, so it’s easier not to think about it or you’ll lose your mind. But when you don’t talk about it, don’t think about it, don’t write about it, that’s when things start to get really fucked up. You need an outlet, you need to be able to have honest conversations about these difficult topics. I think that’s why people find comfort in horror, in transgressive literature, whatever it might be in depictions of violence. It’s a way to process, and sort of come to terms with these very complex and sometimes very frightening but very real and also very legitimate feelings that we all have.

Transgressive does get thrown around a lot and I think half the time people don’t really know how to define it or are mislabeling things. And I think so many writers who may write the most violent, fucked up book, and then you talk to them in real life and they are just the most jovial, down to earth person. Like talking to B.R. Yeager.

A sweetheart.

A total teddy bear!

I’ve had very minimal correspondence with Dennis Cooper… absolute sweetheart.

Prime example.

For me, his books were very big. “I didn’t realize people were writing things like this.”

Yeah, I remember first coming across him when I worked in a bookstore in high school. It must’ve been Frisk. I’d never even heard of him, I just grabbed it cuz the cover looked cool.

Those Grove Press covers for his books are so fucking good.

Exactly! And again, he’s trafficking in very heavy and taboo subjects. The Sluts maybe being the crown jewel example.

I love that book so much.

He’s writing about things that really happen, as disturbing as they are, these are things that really happen, and it’s the people who try to pretend that this stuff doesn’t exist. Those are the ones who are really frightening. The ones who don’t wanna talk about the most serious and evil crimes, those are the ones that you kind of have to watch out for. Just because Dennis Cooper writes about child rape or necrophilia or cannibalism or sado-masochistic sexual stuff. Just because anyone writes about that, that doesn’t mean it’s an endorsement for it.

He's kind of talked about interviews how writing extreme content was meant to represent extreme desire, particularly in reference to George Miles. It’s a lot of that very extreme possession comes out in the form of violence. I’ve always kind of felt that violent in fiction is very emotionally expressive. You can do some pretty poignant things while also being vile if you know what you’re doing.

It's a powerful tool for any artist in any medium, and it’s something we’re so steeped in as a culture it’s almost inescapable. We’re confronted with so much violence on a daily basis, absolutely saturated in blood. So, I think it’s only natural, especially as American writers. It’s something we have to grapple with in whatever way, shape or form it takes.

Crisis Actor was more about political violence, I guess you could call it. Well, The Backwards Hand too. I guess they deal with different kinds of violence.

One of the things that really blew my mind in The Backwards Hand is that the job in Crisis Actor is real. I’m sure you embellished quite a bit in the book, but when I read it, there wasn’t a part of me that thought, “oh I wonder if Matt has done this job before.”

You’d be surprised by how much of Crisis Actor is almost verbatim pulled from those experiences. That book, I call it a novel but it really skews closer to real life. Working that job was very strange and it became a very fertile ground for my imagination. As I was sitting around in gore make-up and prosthetics during a mass-shooting simulation; there’d be times I’d be playing a dead body, literally just having to lie there, covered in blood, of course my mind would wander. So that’s when I started cooking up that book.

But yeah, those experiences were pretty wild. I think, formally, Crisis Actor was where I really found that collage style that I became so taken with and that certainly fed into The Backwards Hand. Working in that mode, that sort of collage, fragmented style was something that really clicked with me. So Crisis Actor became this great launching pad for The Backwards Hand, one being “novel” the other being a memoir, but both incorporating a ton of outside research and being presented in a fractured, fragmented form.

I love that form too, it works so well. I think The Backwards Hand a bit more fluid—you can kind of take paragraph by paragraph as is vs. something like…if someone just handed you list of objects from [Marina Ambramovic’s performance piece, Rhythm 0] you might just be like, “what do you want me to do with this?”

I think you’re absolutely right. Crisis Actor, by design, is a lot more chaotic—almost way more schizophrenic. That book really started as a stack of notecards that I would randomly shuffle around.

The very first draft of Crisis Actor didn’t have any of the speaker tags—what kind of look like the email messages in the book. That came way later. The guys at Tragickal suggested that. I think it was a great suggestion, but originally none of the quotes were attributed, and it was just an absolute chaotic jumble of all this stuff swirling around, and I wanted it to be—in my head, the voice of that book was much more out there and “crazy” for lack of a better word. So I wanted it to be more slippery territory for the reader, whereas Backwards Hand, I was much more conscious of finding connective tissue; finding the scaffolding. Even though it’s a lot of seemingly random information, I’m trying to have a more solid foundation. Like I said, the connective tissue is stronger, so hopefully that leads to a smoother experience for the reader. Also, with it being a memoir, even though I’m pulling in all this stuff from different time periods and different subjects, I had the adventage of my personal narrative acting as the anchor. That was one choice I made from the get-go: when I tell my story, it’s going to be linear, I know where its going from point A to point B. I’m gonna use that as a way to kind of help orient the reader and just act as a solid throughline that can run through the whole book from start to finish. I think it gives it makes it a little easier than Crisis Actor to trace through.

I wanna focus on horror movies for a little bit because they really are a major aspect of the book, and when you think about it, all this started at the beginning of cinema. When you think about it, motion pictures as we know them have only existed for a hundred years, a little more than that…

There’s actually a Lumiere bros film, one of the very first films, it’s called The Devious Cripple, or something. That’s probably a bad French translation, but yeah, The Devious Cripple, about someone pretending to be crippled so they can beg for money on the street. A lot of these early silent films also played into the opposite spectrum of horror—they were comedies. A lot of these short films about “the blind man’s dilemma;” a woman cheating on a blind man, sort of running around right under his nose and he can’t see it. Things like that. Using the crippled body for a comedic effect. On the flipside, because comedy and horror play nicely together—

They’re very closely related. It’s about expectation and timing.

Set up, execution, yeah. You also start to see instances of disfigured villains very early: the Phantom of the Opera, the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Even Nosferatu is sort of taking a human form and corrupting it. Many of the pre-code horror films as well as the classic Universal movies; it’s all about monstrous bodies, whether or the Creature from the Black Lagoon or the Wolfman or Frankenstein. It’s taking a human form and turning into something familiar but also… uncanny maybe isn’t the word. But from the get-go, as you pointed out; an easy way to scare people is to show them a monstrous, disfigured body. You see it through any era of horror films whether it’s the 1950s Golden Age or Atomic Age monsters; a nuclear accident or an experiment gone wrong has mutated the human form into something that it shouldn’t be, but it is. “This creature shouldn’t be walking around, but it is. He could be just like you.”

It goes all the way into slasher films too. All the key slasher franchises: Nightmare on Elm Street and Freddy Krueger, Friday the 13th and Jason Voorhees, Leatherface and the Texas Chain Saw Massacre; the bad guy is always deformed. He’s often hiding behind a mask. It’s almost become a cliché, it’s so pervasive. It kind of goes back to what you said earlier about the disabled body as spectacle, that I think traces its roots in freakshows: it’s something forbidden—it’s something you’re not supposed to see—and that makes you want to see it all the more. That’s part of the appeal of horror films; you’re seeing something you’re not supposed to see, you’re seeing the human body in ways it’s not supposed to look; the human body operating in a form its not supposed to take, this corruption of the flesh, and again, the idea—and you see this in the film, FREAKS. That’s sort of the big moral of that story: this could happen to you. You’re this close to being this monstrous freak.

But then on the other hand, Freaks is kind of progressive in this weird way. Like you point out in The Backwards Hand, the movie shows the “freaks” to be a self-sufficient community.

That’s why I especially admire Tod Browning as a director. Despite that ultimately the freaks are the villains of the film, they enact their bloody revenge at the end, he treats with such humanity. He really took care to humanize them and treat them with dignity. This is something that is so rare, not just in horror but I think in film in general. I think there’s a statistic that’s like, 95% of disabled characters in film were played by able-bodied actors. There’s even this ration of like, “oh if you played a disabled character you have a 7 out of 10 chance of winning an Academy Award.” So there’s a huge representation problem. Even though horror films co-opt the disabled body and use disfigured villains, they’re very rarely played by people who are actually disabled, it’s always make up, right? So, Freaks is a pretty rare example of not only using disabled people in prominent roles, but having virtually the whole cast be made up of a wide variety of disabled people with different conditions. So that’s why I find it to be such a fascinating and important film.

Being made in the 1930s, almost a hundred years ago, and being strangely progressive. It really doesn’t go into horror territory until the final act.

It really does takes it time. It’s been a very long time since I’ve seen Freaks, but from my memory, it’s a lot of that one beautiful woman getting to know this big cast of characters while building towards something.

Yeah, it shows them just going about their daily lives. They’re doing laundry, cooking food, just hanging out together, working. It doesn’t rely on sensationalizying them. It treats them in a very normal way.

You hardly see a disabled character in film whose disability isn’t somehow hinging on the plot. To bring it into a more contemporary frame; there’s been a lot of people applauding better representation today, in horror specifically, and the example I see thrown around a lot is A QUIET PLACE, which is a film I wasn’t particularly crazy about. I liked elements of it, but overall it didn’t totally work for me—that’s besides the point. The young woman who plays the daughter, who is deaf… a lot of people applauded that: “this a big leap forward for horror films. They cast a real deaf person to play this character,” but again, the fact that she’s deaf is a plot device. Oh, she can’t hear the scary monsters! She can’t speak!. You very rarely see a disabled person and their disability isn’t somehoew called out or somehow used in the plot. So it’s kind of mixed; yes, it’s good that there’s more representation in a film like A Quiet Place or The Last of Us—there was that episode where there was a young deaf actor that they used. Yes, it’s good that we’re seeing actual disabled people.

Did you see that film, Run?

No, but I’m familiar. That’s the Hulu movie about Munchausen by Proxy?

Yes. They used a real disabled actor, but again it’s a plot device. I’d love to see, like Freaks, just a depiction of disabled people living there lives and it has nothing to do with the plot. So that’s why I applaud Freaks, for the representation. People argue that it’s exploitative. I kind of see it differently.

Yeah, I can definitely see that. In terms of horror though, in a way it’s an inherently exploitative genre. Regardless of what the subject matter is, you’re going to be exploiting something because you’re taking something that is inherently “not okay” like murder, and you’re saying “here, it’s fun.”

Yeah, this is where a lot of criticism of horror comes from. How can you say this is entertainment? How can you say this is art? This belongs in the gutter, this is just blood and guts, it’s pornography. But I think for a lot of diabled people, myself included, itbecomes comforting because it’s a vessel in which we can channel otherness. I think a lot of people respond to horror movies in this way. You see a lot of queer studies tying into horror, people from the queer community saying they love the horror genre for a similar reason. A feminist approach to horror, again for a similar reason.

When in your real life you are othered for whatever reason that may be—for whatever way you were born that goes against the status quo, and you see it celebrated on the screen, it’s a way to reflect your own experiences as being othered. I think that’s why you have people from marginalized groups empathizing with the villains of horror films. That’s why we love Jason Voorhees, tha’'s why we love Leatherface: they’re going against the status quo. We’re rooting for the monster. That’s sort of what makes it fun to kind of relish in that, because we don’t get that in our day to day existences. We aren’t celebrated for that otherness. I think that’s why it’s something that has always attracted a certain type of person, and I think that’s why its so popular.

One of the things I look at in the book is the of “what does it mean to be disabled” and I think a lot more people are probably disabled in some fashion than they might even acknowledge or realize, and if you’re not currently, you will be at some point. I promise you. Your body is gonna break down, you will degenerate. That’s a given. It sort of goes back to what we were talking about about transgressive fiction, that it’s therapeutic, it’s a coping mechanism, it’s a kind of way to work through these problems we have in terms of our identity, feeling like we don’t fit in or feeling like we’ve been ostracized or demonized. Horror flips the scripts and inverts a lot of these societal pressures that are put on us.

As long as there are people who are othered in that way, horror will continue to resonate.

***

The Backwards Hand is available through Northwestern University Press:

https://nupress.northwestern.edu/9780810147157/the-backwards-hand

/